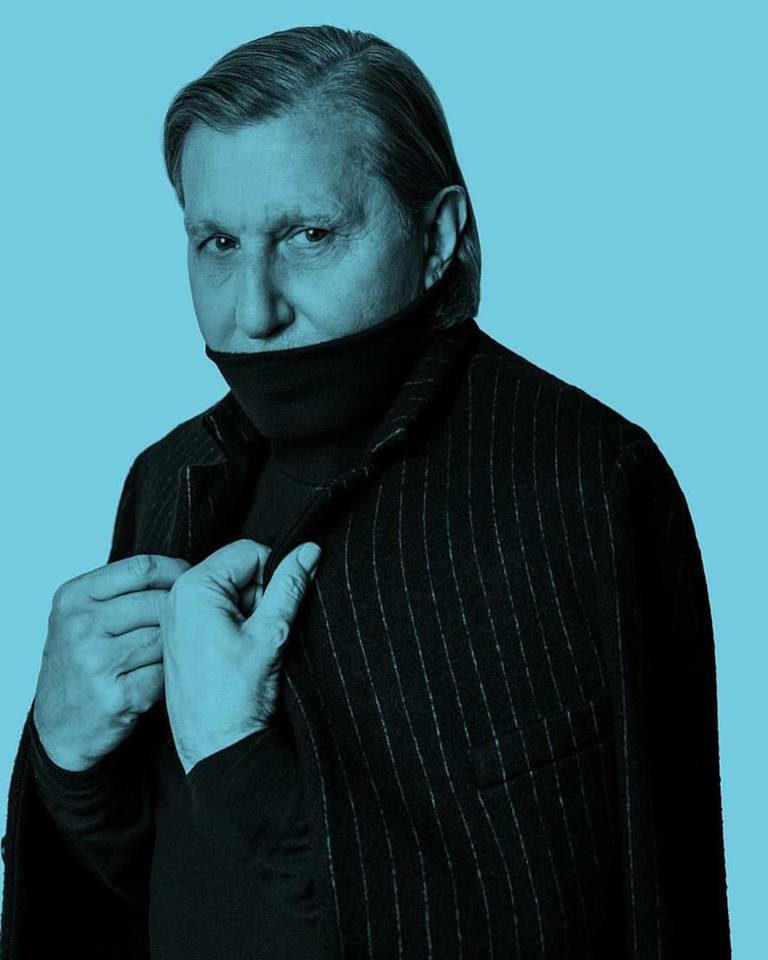

Când vorbești despre Vlad Ivanov, vorbești despre modestie și sinceritate. Asta pentru că actoria reprezintă pentru el omenie, autenticitate, dragoste, conștiință de sine. Toate aceste valori ambalate într-un entuziasm de adolescent.

Succesul nu l-a doborât. L-a construit spiritual. Și-a dat seama de omul care este și de cel care vrea să fie. Își face meseria din credință și ardere interioară, iar despre adevăr spune că e cea mai frumoasă emoție.

Actorul Vlad Ivanov, despre perseverență, succes și autenticitate.

“Dacă ai pasiune, măcar pleci la drum. Și drumul e cel mai important.”, spuneați într-un interviu. Cum v-a ajutat pasiunea să vă urmați drumul?

Cred că lucrurile astea se completează unul pe celălalt, și ca să urmezi un drum spiritual, care ține de ceea ce vrei să faci, e musai să-ți placă ce faci, ca să găsești pe drumul ăsta multe lucruri frumoase. Și dacă mături strada trebuie să o faci cu pasiune. “Și un cizmar e artist în felul lui dacă își face bine și cu drag meseria”, spunea un mare actor.

A fost un drum presărat și cu anevoioase sau doar bucurii?

Pentru că viața noastră este foarte mediatizată, toată lumea are impresia că în jurul nostru sunt numai covoare roșii, aplauze, premii, petreceri. Nu sunt. Sunt lucruri simple, frumoase, adânci, ca în jurul oricărui om. Noi, în schimb, ne aplecăm cu mai multă sensibilitate asupra unui lucru. Cel mai frumos lucru care i se poate întâmpla unui artist e să rămână normal, să rămână ancorat în normalitate, să știe să gestioneze foarte bine succesul, să îi răspundă fiecărui om care-l abordează pe stradă.

V-au adus vreodată în deznădejde obstacolele?

N-aș spune chiar deznădejde, aș spune dificultate.

Dar nu v-au demoralizat.

Nu. Doar m-au pus pe gânduri. Făcând meseria asta din credință și dintr-o ardere interioară puternică, nu cred că poți fi la pământ total după o zi de filmare sau un spectacol care nu-ți iese. Cred că e doar un pas înainte și poți să fii doar obosit sau trist, dar niciodată sfârșit.

Pasiunea vine și cu o doză de entuziasm. Uneori, entuziasmul te poate urca sau doborâ. Dumneavoastră cum îl gestionați?

Entuziasmul e un lucru foarte frumos, mai ales la o vârstă fragedă. Când am început eu, în adolescența mea, undeva pe la 15 ani, cursurile la Școala Populară de Artă, țin minte că aveam un entuziasm enorm. Fugeam de la liceul unde învățam la Școala Populară de Artă în șapte minute pentru a ajunge la cursurile de actorie. Asta înseamnă entuziasm, să vrei să faci cu toată ființa ceea ce ți-ai propus.

Ce spuneau cei din jur despre entuziasmul pe care îl aveați?

Unii mă priveau ciudat, ca pe o ciudățenie. Profesorul meu, Teodor Bădescu, era foarte încântat, dar era un om reținut în a-și arăta dragostea față de mine. Abia după ce a murit am aflat de la soția și fiica lui că m-a iubit enorm, și exigența asta a lui vis-a-vis de mine însemna o dragoste părintească. A fost un profesor de teatru care mi-a deschis multe orizonturi, multe lumi. Perioada aia a fost perioada în care am crescut mult interior și m-a pus pe șine, am înțeles ce înseamnă valoarea autentică a artei.

Dânsul este unul dintre oamenii care v-au deschis calea. Care sunt cei care v-au îndrumat în parcurgerea ei?

Am avut șansa să-l întâlnesc la Botoșani pe Dan Puric. Datorită lui am ajuns în București. Am ajuns să jucăm un spectacol la Teatrul Național, am intrat la facultate și acolo am întâlnit un alt om minunat cu care am legat o prietenie de-o viață, profesoara mea, doamna Sanda Manu și, bineînțeles, după aceea și regizorii cu care am lucrat atât în film cât și în teatru, fiecare a pus câte o piatră la temelia mea ca actor și ca profesionist. În teatru au fost Alexandru Tocilescu, Andrei Șerban, Alexandru Dabija, iar în film Cristian Mungiu și Corneliu Porumboiu. Sunt oameni cu care lucrez absolut excepțional și care dacă m-ar solicita aș spune 90% “Da!”.

Părinții v-au susținut în ceea ce vă doreați?

Da. Din păcate, e o meserie ce ține de vocație. Susținerea a fost una morală, iar material atât cât au putut și ei. Dar lucrurile țineau foarte tare de umerii mei, în funcție de ce puteam să fac.

Când vă uitați în urmă, la copilărie, ce simțiți că ați luat peste ani și ați plantat în munca dumneavoastră?

Cred că am reușit să rămân adolescentul ăla plin de viață, de emoție, plin de entuziasm. E important ca la orice vârstă să-ți păstrezi entuziasmul și emoția aia curată, chiar dacă nu mai e chiar ca atunci, nu mai e intactă, dar sâmburele ăla trebuie păstrat pentru că e o meserie atât de frumoasă și plină de bucurii!, nu ai cum să o faci cu sufletul întinat.

Care sunt cele mai frumoase amintiri din perioada aceea la care vă gândiți cu dor?

Întâlnirile cu verișorii mei. Eram niște “draci de copii”. Ne cățăram peste tot prin copaci, veneam juliți acasă, murdari de dude pe la gură, cu tricourile pătate. Dar eram fericiți. Plecam câte o zi întreagă și veneam seara. Eram generația cu “cheia de gât”. Erau vremuri destul de grele și trebuia să avem grijă noi, frații mai mari, de cei mai mici. Lucrurile se petreceau cu un soi de normalitate. De fiecare dată când ajung acasă, la Botoșani, revăd toate locurile și năzbâtiile pe care le făceam. Trec pe la Școala Populară de Arte, pe la Liceul Pedagogic și mă bucură să retrăiesc perioada aia.

Care a fost elementul care v-a pus față-n față cu teatrul?

A fost o dorință puternică de a face teatru. De mic eram foarte vesel și pus pe glume. Lucrurile au devenit puțin mai serioase în perioada liceului când am început să dramatizez fel de fel de scenete pentru serbările școlare. Intrasem într-un cenaclu literar la liceu și profesoara de atunci mi-a spus că ar trebui să fac ceva mai serios cu lucrul ăsta pentru că am talent. Într-o zi, am văzut în ziarul local, “Clopotul”, un anunț care spunea că Școala Populară de Artă dă concurs de admitere pentru grupa de actorie-teatru. Mi-am spus că e un prilej bun să mă duc puțin mai departe cu joaca asta.

Talentul a fost moștenit?

Sigur că a fost moștenit, dar încă nu știu de la cine (râde). Talentul ți-l dă Dumnezeu sau ți-l dă mama din burtă. E moștenit, dar nimeni din familie nu a profesat.

Concursul de admitere la facultate a fost hopul care trebuia trecut pentru a vă îndeplini visul. Pe lângă asta, mutarea dintr-un oraș de provincie în capitală cu siguranță nu a fost ușoară. V-ați angajat la o consignație în Gara de Nord. Cum ați reușit să vă acomodați?

A fost și bine, a fost și rău. A fost bine pentru că, dincolo de tot vacarmul ăsta al marelui oraș care m-a luat prin surprindere, în prima parte a șederii mele în București am avut parte de o întâlnire absolut extraordinară cu doi oameni care mi-au oferit relaxarea financiară de care aveam nevoie ca să pot să-mi urmez cursurile de audient la clasa lui Dem Rădulescu. Patronii de la consignație, când au aflat că vreau să lucrez pentru a mă întreține la facultate, au fost foarte impresionați și m-au susținut foarte mult. Au fost ani frumoși.

Ați dat de patru ori admitere la facultate.

Am înțeles într-un final de ce nu intru. Am fost audient la clasa lui Dem Rădulescu după ce am picat a treia oară primul sub linie. În anul acela am înțeles mecanismul concursului de admitere și mi-am dat seama ce își doresc de la tine. Nu m-am demoralizat niciodată când am picat la facultate.

De ce nu ați intrat din prima?

Eram extrem de emotiv și veneam dintr-un oraș liniștit, curat, verde, plin de oameni senini, iar Bucureștiul m-a speriat foarte tare la momentul respectiv. Emoțiile mă paralizau. Dar după aceea am învățat să mi le controlez și să pot să înțeleg exact ce-și doreau profesorii de la mine.

Să fi fost spiritul care v-a ținut visurile treze?

Numai Dumnezeu știe. Se poate, totul e posibil în meseria asta care e atât de miraculoasă și plină de necunoscut, încât niciodată nu știi cum de ți se întâmplă. De fiecare dată când avem o seară bună pe scenă spunem că “în seara asta a coborât Dumnezeu pe scenă”. Cred că cineva acolo sus mă iubește.

Ce faceți când dați de greu, când gândiți că nu mai puteți?

Am învățat să mă opresc, să mă gândesc la ceea ce se întâmplă, să înțeleg și să găsesc puterea să merg mai departe. În momentele grele nu e bine să dai mereu cu capul de zid. E bine să te oprești și să înțelegi exact în ce punct al vieții tale te afli. Să o iei cu răbdare de la capăt. Andrei Șerban spune că meseria asta ține și de religiozitate. E ca un ritual pe care îl faci în fiecare spectacol, în fiecare reprezentație. Trebuie să fie ceva sfânt în ceea ce faci, ca să poți transmite energie publicului. Altfel, toată energia aia din scenă nu se transmite.

Vlad Ivanov parcă e omniprezent în cinematografia românească în ultima vreme. Vă fură inima mai mult ecranul decât scena?

Niciodată! E un lucru de conjunctură. Pur și simplu se întâmplă ca de doi ani de zile să fac mai mult film, dar, în același timp, am bucuria să fac măcar un spectacol în fiecare an. Anul acesta, din păcate, nu am mai reușit.

Care au fost poveștile filmelor în care ați jucat care v-au impresionat cel mai mult?

Fiecare poveste m-a impresionat de vreme ce am acceptat să joc. De nouă ani de când sunt liber profesionist, urmăresc, în primul rând, să-mi placă povestea, să-mi placă personajul pe care urmează să-l interpretez. Să-mi placă în sensul de bogăție interioară. Să fie un personaj care, indiferent de ponderea lui în film sau în teatru, să rămână în sufletul spectatorului. Desigur, contează și regizorul, și actorii cu care lucrez, dar, în special, povestea e cea care mă atrage foarte tare.

Care a fost personajul în care v-ați regăsit cel mai bine?

În teatru m-am legat foarte tare de Ivanov – nu neapărat pentru că are numele meu de familie, dar am empatizat foarte bine cu stările personajului, cu durerile și cu trăirile lui. Dar nu aș minimaliza. Nu aș putea alege. E ca atunci când ești mamă, ai patru copii frumoși și cineva te întreabă pe care îl iubești mai mult. Nu poți alege.

Cum decurge cunoașterea personajului de la documentare până la interpretare, atât în film cât și în teatru?

Perioada de documentare e una dintre cele mai frumoase, pentru că începi să îl gândești foarte serios, să aduni date despre personaj, să îi creezi o biografie, să ii descoperi viața, să îi descoperi mersul, gesturile, felul în care vorbește, în care tace, în care privește. Toate lucrurile astea fac parte dintr-o bogăție interioară pe care trebuie să o ai tu ca actor. Trebuie să fii ca un burete care absoarbe toate aceste lucruri. Și nu neapărat numai în perioada în care lucrezi la un rol. Un actor nu ar trebui să meargă indiferent pe stradă, el trebuie să fie atent la tot ce se întâmplă în jurul lui.

Puneți câte ceva din realitate în fiecare personaj.

Sigur că da. Și din trăirile mele, din experiența mea de viață. Un actor trebuie să fie foarte bogat în interior, cu tot soiul de senzații, emoții, ca să poată să scoată din el. Lucrăm cu sufletul, cu mintea, corpul nostru. Mai contează foarte mult și discuțiile cu regizorul, ceea ce-ți cere, ce crede el.

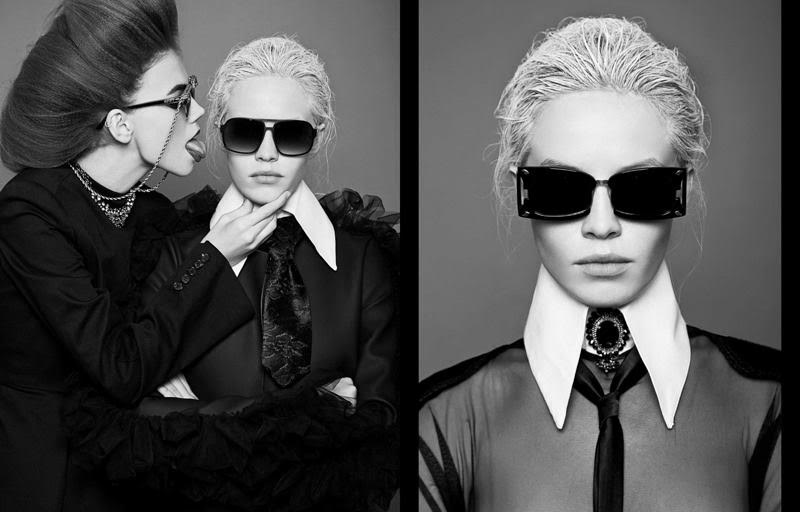

photo: Matei L. Buta

Am aflat din discuțiile cu Daniel Sandu, regizorul filmului, că acest părinte slujește la o biserică din Roman și că aș putea să mă duc să-l văd sau chiar să și vorbesc cu el. Dar noi nu ne-am dorit să facem o copie fidelă a părintelui, nu ne-a interesat acest lucru, ne-a interesat „discursul” lui și felul în care își mână „oile” către credință. Am căutat împreună tot soiul de resorturi interioare, am încercat să înțeleg de ce acționează așa. Mi-am dat seama că el nu este un om profund rău, numai că mijloacele lui pedagogice sunt greșite.

Care au fost cele mai dificile părți ale personajului?

Trecerile lui foarte puternice, extrem de bruște. Sunt câteva secvențe extrem de intense în film, care au făcut și deliciul meu, dar și al filmărilor. Mi-a plăcut foarte mult la părintele Ivan felul în care trece cu atâta ușurință și seninătate de la o stare la alta.

Care a fost scena preferată?

E o scenă care m-a emoționat foarte tare, atunci când Ivan își dă seama că cei doi seminariști, Gabriel și Tudor, au complotat împotriva lui, iar el, disperat fiind, își dă seama că și-a pierdut total autoritatea și nu mai are niciun fel de putere asupra elevilor. După ultima dublă toți actorii tineri care erau în sală au început să aplaude. A fost un moment extrem de emoționant pentru mine.

Ați lucrat cu actori foarte tineri. Cum a fost să participați la dezvoltarea lor atât profesională cât și personală?

Nu pot să am decât cuvinte de laudă pentru ei. Am avut temeri înainte pentru că e destul de greu să găsești deocamdată, în România, tineri care să nu fie actori și să poată să fie actori. Cred că doi dintre ei erau actori, unii au devenit pe parcursul filmării odată cu intrarea la actorie. Au contat enorm de mult repetițiile cu ei de dinainte de filmare. Practic atunci am început să ne armonizăm unul cu celălalt, să înțelegem rolul fiecăruia în acest puzzle al filmului. Mi-am dat seama că în urma fiecărui calup de filmare, deveneau din ce în ce mai serioși, mai motivați, mai profunzi. Pentru ei a fost clar o experiență unică, de viață.

Ce credeți că i-ar mai trebui cinematografiei românești să ajungă cât mai sus?

Sunt multe lucruri care țin de sistemul cinematografic care la noi încă nu funcționează. S-au încercat să se rezolve, dar nu s-a putut. Suntem bucuroși că putem face filme măcar în stadiul în care suntem.

Ce vă motivează de zi cu zi?

Întâlnirile cu oamenii sinceri, oamenii calzi, fără măști, nu contrafăcuți.

Care e cea mai frumoasă emoție?

Adevărul. Dacă ești autentic, și emoția e la fel.

Vă considerați un om fericit?

Fericirea e în lucruri mici, lucruri care pentru mulți nici nu contează. Cred că e vorba mai mult de împlinire sufletească.

Cu ce te bucură fotografia de fashion?

Cu ce te bucură fotografia de fashion?